Why we advocate for more than local Filipino American history...

The activists of Little Manila are dedicated to bringing multifaceted equity to Stockton. After generations of neglect of communities in the margins and the notion that diversity is a hindrance to progress, we believe in cherishing all communities and that diversity is our city’s greatest asset.

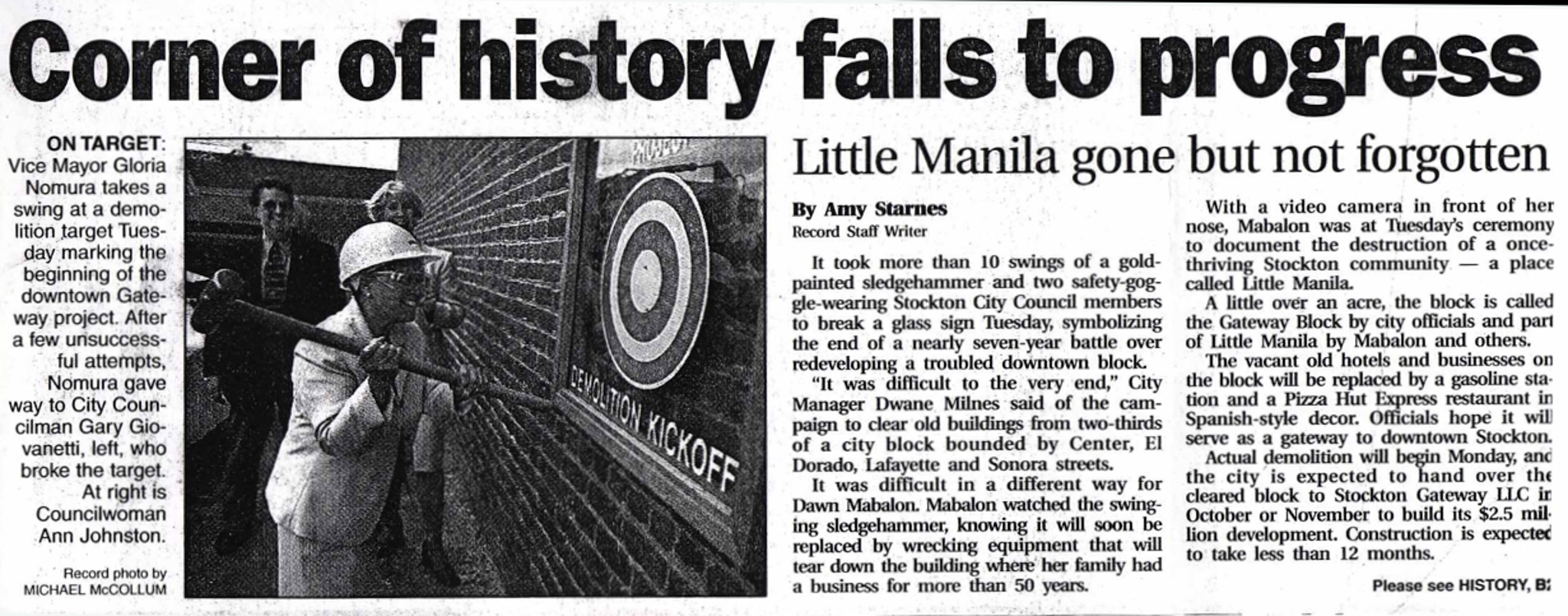

In 1999, when two newly graduated college students, Dawn Mabalon and Dillon Delvo, returned to Stockton after learning about the significance of their hometown to Filipino American history, they literally found demolition equipment in front of buildings of what remained of the Little Manila community, the largest population of Filipinos in the world outside of the Philippines from the 1920s to the 1960s. They figured that someone should do something about this, so they started Little Manila Rising.

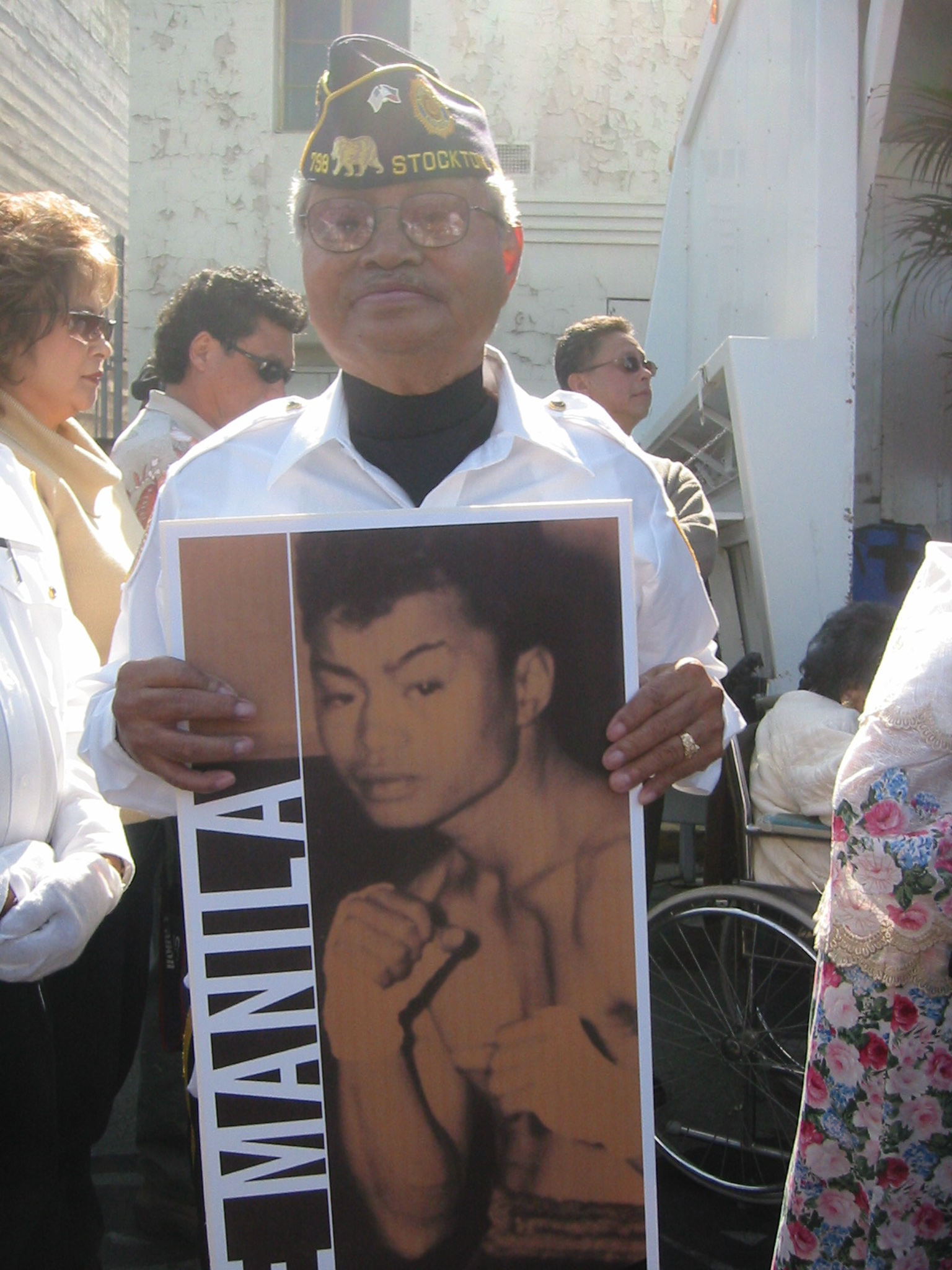

They watched the buildings of one of the last remaining blocks in Little Manila get demolished to build a McDonald’s restaurant and gas station. To them, they were not just buildings, but they were the last remnants of the Manong/Manang Generation. The first generation of Filipinos to come to America in the 1920s and 1930s who worked backbreaking work in the fields of California in order to help their families in the Philippines. The Philippine-American War left the country devastated in the 1900’s leaving a generation of Filipinos with little economic opportunity. These manongs & manangs (mostly manongs since the ratio of Filipino men to women was 20 to 1) left their homes as teenagers and young adults, many never seeing their families again.

“To them, they were not just buildings, but they were the last remnants of the Manong/Manang Generation.”

The work of the manongs and manangs would establish agriculture as the largest industry in California. They would fight injustice, forming farm labor unions and creating change for acts that would be considered inhuman today. Their activism would lead to the establishment of one of the largest social justice movements in American history, the joining of the Filipino farm labor union led by Larry Itliong and Mexican farm labor union led by Cesar Chavez to form one union, the United Farm Workers.

Watching the buildings being destroyed, Dawn and Dillon vowed that the destruction would end there. Much of Little Manila was already destroyed in the early 1970s by the building of the Crosstown Freeway. Like other neighborhoods of color throughout America, decision makers built a freeway through it, destroying family homes, businesses, community centers, and much more in the name of progress.

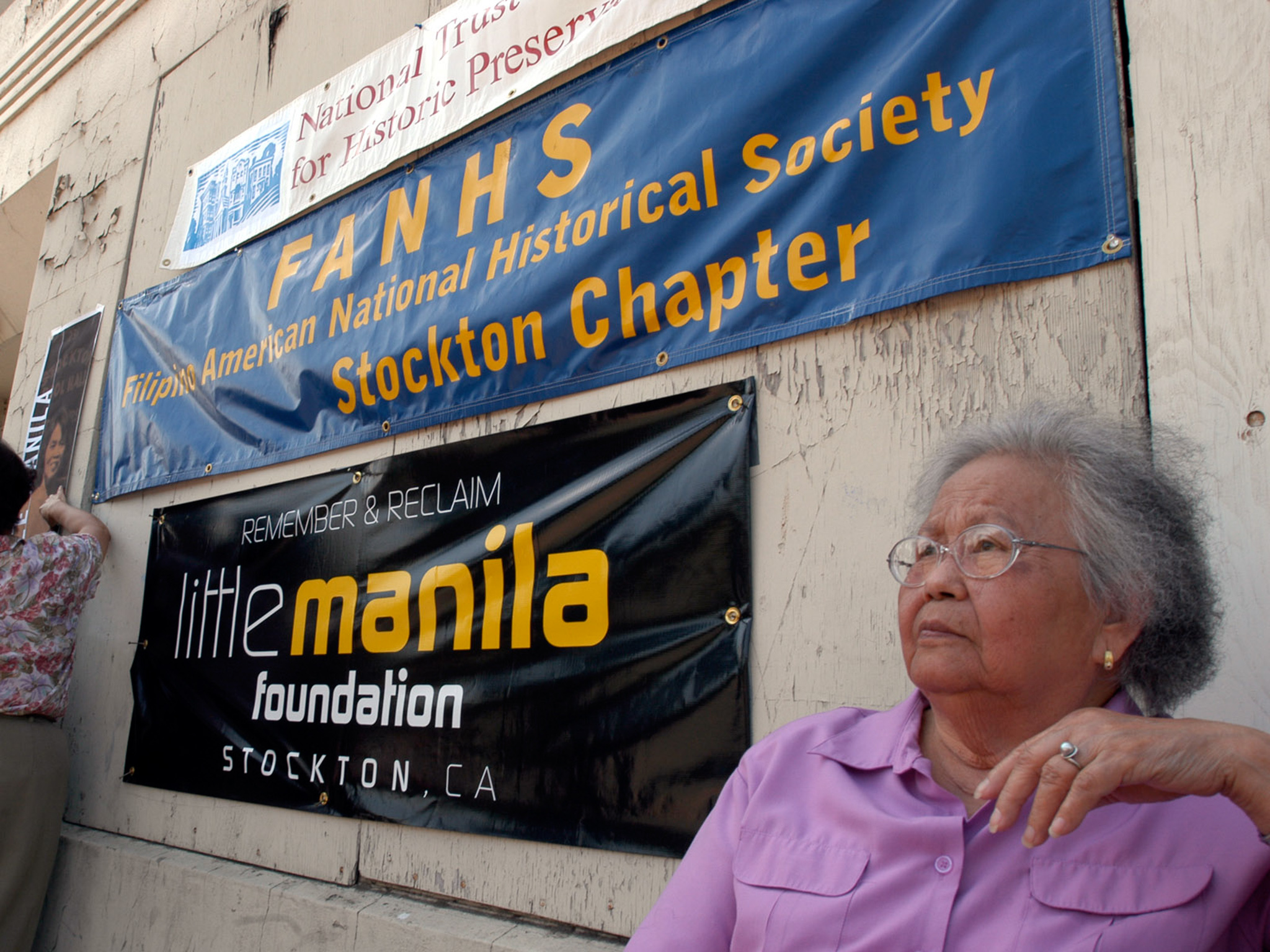

In 2001, they rallied the community together to have the city designate the site as the Little Manila Historic Site. They began to sell Little Manila T-shirts to raise money to mark the area with banners and let people know of its significant history. In 2002, they dedicated the historic site and unveiled the banners. And in 2003, the City of Stockton named the area a commercial redevelopment zone with a developer who planned to tear everything down in order to build an Asian-themed strip mall. The plan was to destroy eight square blocks that consisted of family homes, businesses, churches, non-profits, and the historic buildings of Little Manila.

With only four months to respond with a counter-proposal for redevelopment of the area, Little Manila activists got to work knocking on each door of every person in the affected area and invited them to be a part of envisioning what they would like to see in their community. Little Manila held three three community charrettes attended by over 200 people at each event. The National Trust for Historic Preservation named Little Manila “one of the eleven most endangered historic sites in America.” The story became an international story, leading the city to receive the most letters ever written against a city proposal. The exposure allowed a like-minded smart growth developer that saw adaptive reuse of historic sites as a benefit to the development plan. And in October 2003, Little Manila submitted their counter proposal to the strip mall development.

“The National Trust for Historic Preservation named Little Manila one of the eleven most endangered historic sites in America.”

In the end, the city chose neither proposal and did not move forward with redevelopment of the area. Little Manila viewed this as a victory especially since the strip mall developer was the former boss of Stockton’s city manager at the time. Also, this was at a time when sprawl development in Stockton was at an all-time high. It was the fastest growing city in America at one point. All of which helped to contribute to the largest municipal bankruptcy in America (2012) prior to the City of Detroit’s bankruptcy.

In the beginning, Little Manila activists were involved to save a few buildings and protect the legacy of their ancestors. But in order to do that, they had to address the root of much of Stockton’s problems - the consistent disenfranchisement of the poor and institutionalized racism.

In the first half of the 20th century, Main Street was the dividing line for people of color in Stockton. If you were a person of color in 1930, the unspoken law was that you were not welcome north of Main Street, which is why communities of color existed to the South. That mentality transferred to the Crosstown Freeway in the late 1960s, with racial lines being replaced by class lines. The Crosstown Freeway not only destroyed Little Manila, but also Chinatown (Stockton had the third largest Chinatown in California), and Japantown. It is also important to note that there were two other options for placement of the Crosstown Freeway, which both would have no where near the devastative impact as where the freeway is today.

“...they had to address the root of much of Stockton’s problems - the consistent disenfranchisement of the poor and institutionalized racism.”

In saving the historic buildings of Little Manila, activists had to engage a community that always felt under the threat of eminent domain (the city’s ability to seize property and pay the owner its value). Because of municipal neglect, the community had some of the lowest property values in all of Stockton. A large percentage of residents in the area were property owners, many of them from families who had owned their property for multiple generations. With property costs skyrocketing in Stockton, the value of the homes in Little Manila were no where close to the costs of homes in other places, essentially turning long time property owners into renters.

“While Little Manila activists were knocking on doors inviting residents to envision what they would like to see in their community, city council members walked the Little Manila neighborhood notifying residents that their homes would be taken away.”

While Little Manila activists were knocking on doors inviting residents to envision what they would like to see in their community, city council members walked the Little Manila neighborhood notifying residents that their homes would be taken away. It was an unprecedented time of growth at any cost in Stockton. California Rural Legal Assistance successfully sued the city twice for destroying affordable housing without building replacement affordable housing. It was a complete municipal assault upon the most vulnerable communities in Stockton. A moral bankruptcy that would help lead to a financial bankruptcy.

Little Manila’s advocacy is based upon this early experience. The erasure of Filipino American history in the streets of Stockton was not an isolated matter. It was a part of a larger accepted norm in the city of Stockton, that the poor and people of color and their histories are unimportant. In fact, they are often seen as an obstacle to progress.

The activists of Little Manila are dedicated to bringing multifaceted equity to Stockton. After generations of neglect of communities in the margins and the notion that diversity is a hindrance to progress, we believe in cherishing all communities and that diversity is our city’s greatest asset.

Once upon a time in Stockton, "progress" meant the destruction of our history, the erasure of the legacy of our ethnic communities, and the building of a McDonald’s. (Stockton Record - May 19, 1999)